Culture

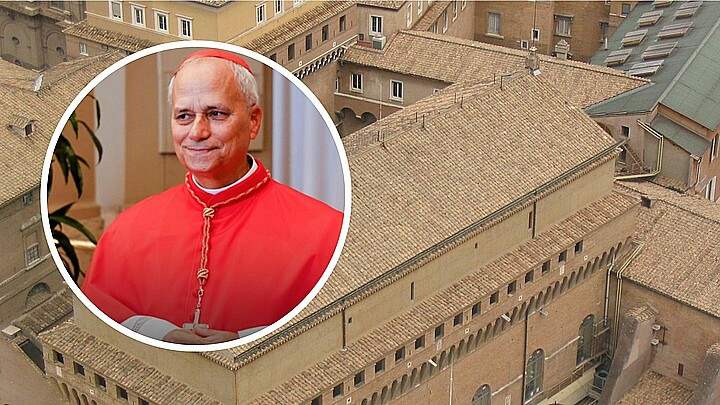

Thomas Jefferson's sophisticated, radical vision of liberty

Thomas Jefferson was born on April 13, 1743. Today the Declaration of Independence still remains radical

April 13, 2023 11:15am

Updated: April 13, 2023 8:58pm

When Virginians reflect on the American Revolution, they often like to describe George Washington as its sword, Patrick Henry as its tongue, and Thomas Jefferson as its pen.

Jefferson expressed a sophisticated, radical vision of liberty with awesome grace and eloquence. He affirmed that all people are entitled to liberty, regardless of what laws might say. If laws don’t protect liberty, he declared, then the laws are illegitimate, and people may rebel. While Jefferson didn’t originate this idea, he put it in a way that set afire the imagination of people around the world, Moreover, he developed a doctrine for strictly limiting the power of government, the most dangerous threat to liberty everywhere.

Jefferson was among the most learned men of his time. He understood historic struggles for liberty. He drew on his practical experience serving as a representative in the Virginia House of Burgesses, the Virginia Convention, Continental Congress, and Confederation Congress, and as Governor of Virginia, Minister to France, Secretary of State, Vice President, and President of the United States.

With his gifted pen and meticulous script, Jefferson drafted more reports, resolutions, legislation, and related official documents than any other Founding Father. Above all, Jefferson wrote letters, probably more than his illustrious contemporaries and a larger number of these letters survive—some 18,000. He corresponded with many leading lights of liberty, including Thomas Paine, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Patrick Henry, Marquis de Lafayette, James Madison, George Mason, Jean-Baptiste Say, Madame de Stael, and George Washington.

He had a reserved manner, even with his children, but he was a steadfast friend. His friendship with James Madison endured for a half-century. Jefferson’s tact enabled him to maintain relationships with prickly-pear patriots like Thomas Paine and John Adams. In an affectionate letter, Adams commended him for “friendly warmth that is natural and habitual to you.”

Jefferson was an instantly recognizable Founding Father. He stood about six feet two inches tall, was thin, had reddish hair, hazel eyes, and a freckled complexion. As a young man, he was a snappy dresser, but in later years he neglected his appearance. His hair turned gray and flopped around his head. When President, he reportedly greeted morning visitors in worn slippers and a worn coat.

Jefferson’s intellectual legacy has been hotly contested. For four decades after he left the White House, his ideas dominated U.S. government policy, and he was revered as the “Sage of Monticello.” Then the Civil War changed everything. Some 620,000 people died amidst that struggle to preserve the Union, turning public opinion against Jefferson who had defended the right of secession and independence. He fell even further out of favor during the “Progressive Era” when reformers imagined that every problem could be fixed by giving the federal government more power. President Theodore Roosevelt scorned Jefferson as a “scholarly, timid, and shifting doctrinaire.” Hamilton, apostle of government power, became the most revered Founder.

The bicentennial of Jefferson’s birth, 1943, prompted many Americans to think about his life, and his reputation experienced a comeback. It was marked by construction of the Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D.C., emblazoned with his stirring oath: “I have sworn upon the altar of God eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” As historian Merrill D. Peterson explained the comeback: “The man glorified in the monument had transcended politics to become the hero of civilization. He had come to stand for ideals of beauty, science, learning, and conduct, for a way of life enriched by the heritage of the ages yet distinctly American in outline. The range of his appeal, if not its intensity, increased with the disclosure of his varied and ubiquitous genius.”

Since about 1960, Jefferson has again come under attack. Constitutional historian Leonard Levy, for instance, cited episodes when Jefferson suppressed civil liberties, especially during his terms as Virginia Governor and U.S. President. Historian J.G.A. Pocock portrayed Jefferson as a backward-looking country aristocrat who feared cities and commerce, out of touch with the modern world. Historian Bernard Bailyn called Jefferson an unthinking “stereotype.”

Some historians revived Federalist charges that Jefferson fathered children with his attractive young slave Sally Hemings. And of course, many historians expressed disgust that Jefferson owned slaves, bred slaves, gave away slaves as wedding presents and never liberated any slaves–he reportedly owned 180 slaves when he wrote the Declaration of Independence and had 260 slaves when he died. Historian Page Smith claimed that because Jefferson didn’t always live up to his expressed ideals, he was a fraud, and his ideals were no good.

Though Jefferson had personal failings—in the case of slavery, a monstrous one—they don’t invalidate the philosophy of liberty he championed, any more than Einstein’s personal failings are evidence against his theory of relativity. Moreover, every one of Jefferson’s adversaries, past and present, had personal failings, which means that if ideas are to be dismissed because of an author’s failings, Jefferson and his adversaries would cancel each other out. When historians finish dumping on Jefferson, they still won’t have cleared the way for Karl Marx or whomever they admire. Jefferson’s accomplishments and philosophy of liberty must be recognized for their monumental importance.

Early Life

Thomas Jefferson was born April 13, 1743, at a plantation named Shadwell, along the Rivanna River. He was the third child of Peter Jefferson, who seems to have been a self-educated, enterprising man-surveyor, plantation operator, judge, and representative in the Virginia House of Burgesses. His mother, Jane Randolph, brought aristocratic blood from a prosperous Virginia family. While Thomas expressed admiration for his father, he hardly ever talked about his mother.

Jefferson was tutored by Anglican ministers in Latin, Greek, science, and natural history. For two years, he attended William and Mary, America’s second-oldest college (after Harvard), located in Williamsburg. Then he began studying English common law and opened a successful law practice.

Jefferson loved books. Among the titles that would influence his understanding of liberty: John Locke’s Two Treatises on Government, Adam Ferguson’s An Essay on the History of Civil Society, and Baron de Montesquieu’s complete works. His library would eventually exceed 6,000 volumes.

Jefferson was in the thick of things politically because Williamsburg was the capital of Virginia, the largest and richest colony. His political career began in December 1768 when he was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses. The hot issue was Britain’s persistent effort to defray its war debts by taxing colonists. Jefferson helped form a committee of correspondence for coordinating tax resistance.

In 1774, Jefferson wrote his first published work, a 23-page pamphlet called A Summary View of the Rights of British America. It was a legal brief that boldly declared that Parliament didn’t have the right to rule the colonies. The work established Jefferson as a man who had a way with words.

By March 1775, Jefferson was named a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in Philadelphia. He met people he had heard much about, especially John Adams, Samuel Adams, and Benjamin Franklin. After meeting the Virginian, John Adams remarked: “Writings of his were banded about, remarkable for their peculiar felicity of expression…. [Jefferson] was so prompt, frank, explicit and decisive upon committees and in conversation … that he soon seized upon my heart.”

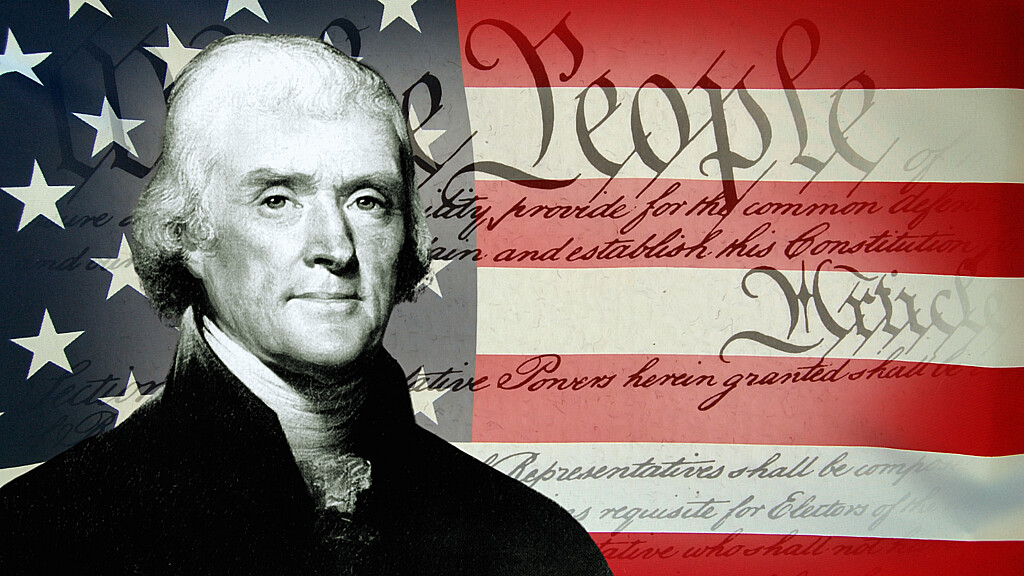

On June 7, 1776, Richard Henry Lee urged the Continental Congress to adopt his resolution for independence. The debate was scheduled for July 1, while Jefferson, Franklin, John Adams, Roger Sherman, and Robert R. Livingston were assigned to prepare a statement announcing and justifying independence.

Thirty-three-year-old Jefferson drafted the Declaration of Independence on the second floor of a Philadelphia home belonging to bricklayer Jacob Graff, where he rented several rooms. They were at Market and Seventh streets. Jefferson wrote in an armchair pulled up to a dining table. He probably scratched away with a goose quill pen, a writing implement that is quite difficult to use. By habit, he did most of his writing between about 6:00 PM and midnight. The Declaration took him 17 days.

Like A Summary View of the Rights of British America, the Declaration was mostly a legal brief listing a succession of complaints against England—revolution wasn’t to be undertaken lightly. In the Declaration, however, Jefferson directed his case against George III rather than Parliament, and he provided more of a philosophical justification for the Revolution.

With just 111 words, he expressed ideas that would inspire people everywhere: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.”

This was radical stuff. It was radical for Jefferson’s day, as subsequent struggles with Federalists made clear. It was too radical for Abraham Lincoln who forcibly resisted the secession of Southern states. Today, it remains a radical creed, since few Americans talk much about the right of armed rebellion against the government.

As Jefferson later explained his aims: “to place before mankind the common sense of the subject, in terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independent stand we are compelled to take. Neither aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.”

All colonial delegates except those from New York, who initially abstained, voted for Lee’s independence resolution on July 2nd. Then came a three-day debate on Jefferson’s draft of the Declaration. Congress voted to cut about a quarter of the text and insisted on many minor changes. Deferring to delegates from Georgia and South Carolina, and perhaps delegates from some Northern colonies that had engaged in the slave trade, Congress cut Jefferson’s extended attack on George III for not outlawing the slave trade.

Congress approved the Declaration of Independence on July 4. On July 19, 56 men officially signed what was to become the most important document in American history.

Jefferson served as Revolutionary War Governor of Virginia, raising money and cobbling together defenses against the British. Moreover, thanks to his efforts, Virginia became the first state to achieve complete separation of church and state.

Amidst these public crises, Jefferson endured shocks at home. He and his wife Martha had three children die in infancy. On September 6, 1782, Martha died at 33—complications from childbirth. They had been married 10 years. Deeply depressed, he stayed in his room for three weeks. Then, for several more weeks, he spent nearly every day alone, riding his horse through the woods around Monticello. It was fellow Virginian James Madison who coaxed Jefferson back into public life.

Jefferson went on to do much more for liberty during his phenomenal career. He represented American interests in Paris while the Constitutional Convention conducted its epic debates, but through correspondence he helped convince James Madison, the architect of the Constitution, to support the adoption of a bill of rights. As Secretary of State in George Washington’s cabinet, Jefferson was horrified at Alexander Hamilton’s scheming to subvert the Constitution and expand federal power. This convinced Jefferson that he must seek the Presidency. He won in 1800, cut taxes, cut spending, and paid off a third of the national debt. When Spain blocked access to the Mississippi and ceded it to Napoleon, then conquering Europe, Jefferson moved to purchase the Louisiana territory, even though he couldn’t defend the policy on constitutional grounds. Unfortunately, his presidency closed on a sour note—frustrated by British seizures of American sailors and goods, he declared a trade embargo that backfired.

After his second term, Jefferson retired to Monticello, his beloved mountaintop mansion near Charlottesville, Virginia. Here he planned the University of Virginia, played with his 13 grandchildren, struggled with his money-losing properties, and wrote many luminous letters.

Jefferson explained his exhilarating vision of liberty, perhaps his most precious legacy to the world. He insisted that liberty is impossible without secure private property: “A right to property is founded in our natural wants, in the means with which we are endowed to satisfy these wants, and the right to what we acquire by those means without violating the similar rights of other sensible beings. . . .”

How gracefully he rejected envious appeals to seize wealth: “To take from one, because it is thought his own industry and that of his fathers had acquired too much in order to spare to others who, or whose fathers have not exercised equal industry and skill, is to violate arbitrarily the principle of association, the guarantee to everyone a free exercise of his industry and the fruits acquired by it.”

Jefferson urged Americans to pursue peace through free trade. “It should be our endeavor,” he wrote, “to cultivate the peace and friendship of every nation … Our interest will be to throw open the doors of commerce, and to knock off all its shackles. . . .”

Personally, the most heartening experience of Jefferson’s last years was the reconciliation with John Adams. It was the idea of Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia physician and fellow signer of the Declaration of Independence. In January 1811, Dr. Rush wrote Jefferson, reminiscing about the Revolutionary days and Adams’ contributions.

Although Jefferson and Adams became bitter rivals for the presidency, Adams later defended Jefferson against attacks from fanatical Federalists. Jefferson, almost 69, told Dr. Rush that while he was wary of the suspicious and envious Adams, then 76, he recognized what Adams had done for American liberty. Not long afterward, a couple of Jefferson’s Virginia friends visited Adams and heard him declare: “I always loved Jefferson and still love him.” Word got back to Jefferson who was thrilled.

Adams ended up writing the first letter on January 1, 1812, and Jefferson replied: “I now salute you with unchanged affections and respect.” Soon correspondence was flowing between Quincy and Monticello. The two men talked about their health, books, history, and current affairs. They touched on past political disagreements, Adams’ persistent pessimism, and Jefferson’s enduring optimism. Above all, they talked about the American Revolution which both men were immensely proud of. “Crippled wrists and fingers make writing slow and laborious,” Jefferson confided in October 1823. “But, while writing to you, I lose the sense of these things, in the recollection of ancient times, when youth and health made happiness out of everything.”

Before Jefferson slipped into a coma on July 3, 1826, he asked: “Is it the Fourth?” He died on the Fourth, about 12:20 PM, a half-century after the glorious Declaration. Meanwhile, in Quincy, Massachusetts, some 500 miles away, John Adams was fading, too. Around noon on the Fourth, some six hours before he died, he managed a few words: “Thomas Jefferson survives.” Indeed he does, in the hearts and minds of millions everywhere who cherish liberty.

Jim Powell

Jim Powell, a senior fellow at the Cato Institute, is an expert in the history of liberty. He has lectured in England, Germany, Japan, Argentina, and Brazil as well as at Harvard, Stanford, and other universities across the United States. He has written for the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, Esquire, Audacity/American Heritage and other publications, and is author of six books.

This article was originally published on FEE.org. Read the original article.