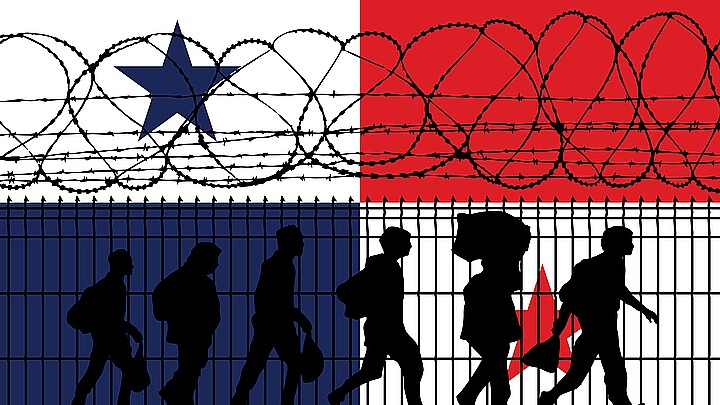

Immigration

Disease risk increases due to closure of Darién Gap migratory crossings between Colombia and Panama

If the number of people traveling along the migratory route increases, the area’s hospital network would collapse

July 12, 2024 4:26pm

Updated: July 15, 2024 9:51am

Endemic diseases such as congenital syphilis, chikungunya, dengue and leptospirosis could increase in Colombia due to Panamanian closures of migratory crossings in the dangerous Darién Gap jungle land bridge, the Colombian Ombudsman’s Office warned this Friday.

That is the jungle route through which thousands of migrants pass every week seeking to reach North America while crossing from Colombia in South America to Panama in Central America. It is the only area between the two regions where there are no paved roads or significant signs of civilization.

ADN America recently reported that Panamanian authorities recently began operations to locate and close some of the makeshift dirt roads created by coyotes to transport migrants from South American to Central America in an effort to curb illegal migration.

In a Colombian government analysis on the violation of human rights due to the Panamanian land closure of the Colombian-Panamanian border in several parts of the Darién Gap, health concerns were raised for nine border municipalities of Colombia, where around 480,000 people live, according to the report.

“If the number of population in human mobility increases, the hospital network would collapse, which is why the human rights institution urges the national government and municipal and departmental health authorities to implement measures that prevent the possible increase in pathologies,” wrote the Colombian Ombudsman’s Office on their website.

The Colombian statement explains that if the closures caused between 10% and 20% of migrants to stay in the Urabá-Darién region, there would be an increase in population, especially in the municipalities of San Juan de Urabá, Arboletes, and San Pedro de Urabá.

In these municipalities, which already have a very precarious hospital system, “there could be an increase in the spread of diseases and difficulties in the hospital network to care for them,” they allege.

The Ombudsman estimates that there could be an increase in the contagion rate of congenital syphilis, with 5.7%; of chikungunya and dengue, 5.2%, and of leptospirosis, 4.7%, per 1,000 inhabitants.

Given the situation, there is a deficit of hospital beds and in municipalities such as Turbo, one of the ports of departure for migrants to the Darién jungle, where there are only 100 beds, an additional 461 would be required.

They added that recent restrictions could trigger a humanitarian crisis, especially affecting public health, making it crucial to address the problems comprehensively.

Last week, ADN reported that the Panamanian government announced new closures of crossings in the Darién, the natural border between Colombia and Panama, with the aim of channeling the migratory flow through “a humanitarian crossing” and thus more easily “protecting” the migrants who cross the jungle, in addition to decreasing their number, in his words.

Last week, the National Border Service (SENAFRONT) had announced the closure of three passes, to which are now added another “four or five” of the routes that migrants use to leave this dangerous and mountainous jungle.

Many people spend days trying to cross the region, exposed to hunger, lack of drinking water, inclement weather and wildlife, but also to criminal gangs and armed groups that control it.

The closure of these unauthorized crossings or trails occurs in the midst of a large flow of migrants through the Darién jungle, through which more than 195 thousand people have crossed this year, most of them Venezuelans and Haitians, while in 2023 there were more that 520,000, an unprecedented figure, according to official data from Panama.