Crime

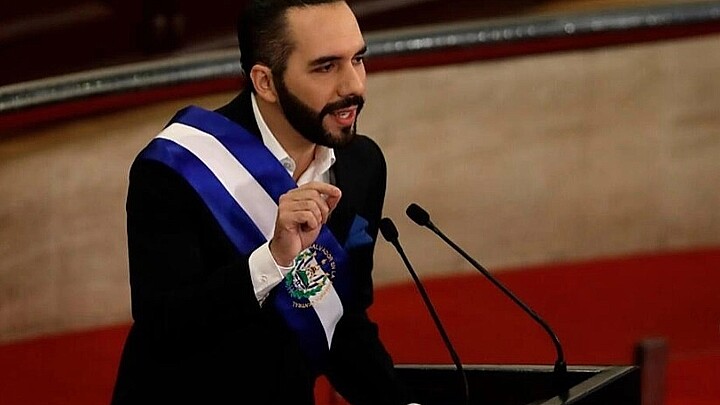

El Salvador: One year after gang-crackdown measures

With a population of 6.3 million, the mass arrests have turned El Salvador into a country with one of the highest prison population rates in the world

March 28, 2023 8:42am

Updated: March 28, 2023 8:42am

El Salvador on Monday marked a full year since the government originally implemented its emergency measures to crack down on gang members, policies that were originally intended to only last one month.

On March 27, 2022, President Nayib Bukele requested special powers to crack down on gangs after there was a surge in homicides in which 62 people were killed in 48 hours.

The special powers temporarily suspend constitutional protections and freedom of association in the Central American country. Additionally, Bukele reformed the country’s penal code to increase jail time for gang members and try minors who are involved with gangs as adults.

One year after the measures were implemented, more than 66,417 alleged gang members have been arrested—about 2 percent of the Central American country’s entire adult population, according to government statistics.

“Now, a year later, we closed with zero homicides, and March 2023 is on track to be the safest month in our history,” Bukele tweeted triumphantly on Sunday.

With a population of 6.3 million, the mass arrests have turned El Salvador into a country with one of the highest prison population rates in the world. In February, El Salvador opened a new “mega-prison” to accommodate more than 40,000 gang members.

While homicides have declined by more than 38 percent since last year, more than 58,000 of the prisoners are still awaiting formal charges or a trial. Several thousands of others do not have the right to consult a lawyer.

Along with the record-breaking number of arrests, however, there have also been 111 deaths of inmates in custody and over 5,802 known cases of human rights violations, according to a coalition of local rights groups.

Some of the criticism of administration's efforts are that some of the arrests appeared to have been based on questionable evidence, such as whether an individual has tattoos or is related to a gang member.

Other arrests have reportedly been made to meet a daily quota imposed on police officers.

The crackdown has led to “mass arbitrary detention, torture and other forms of ill-treatment against detainees, deaths in custody, and abuse-ridden prosecutions,” Human Rights Watch said in a report.

Bukele has given no signs that he intends to end the state of emergency and return to normal police procedures. According to El Salvador’s Justice and Security Minister, Gustavo Villatoro, the state of emergency will continue until the last gang member is captured.