Crime

SPECIAL REPORT: Are the Pandora Papers revealing real crimes?

Latin America’s Pandora Box: The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists has released a treasure trove of secret documents referencing 90 Latin American public officials with offshore interests and tax havens. But are they illegal?

November 23, 2021 2:00pm

Updated: November 23, 2021 6:32pm

Last month, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) released the Pandora Papers, revealing the offshore interests and activities of 35 current and former world leaders, 336 politicians and public officials in 91 countries and territories.

The leak, consisting of more than 12 million documents, reveals how many of the world’s most powerful individuals shelter their assets in offshore accounts, shell companies and real estate investments.

According to the ICIJ, the Pandora Papers “spotlight how deeply secretive finance has infiltrated global politics,” and offer “insights into why governments and global organizations have made little headway in ending offshore financial abuses.”

In Latin America, the revelations have been particularly far-reaching and individuals at the highest levels of power have been brought under public scrutiny. Of the 330 politicians and public officials mentioned in the papers, 90 are Latin American. This figure includes three current presidents, 11 former presidents, a finance minister and a central bank governor.

The papers raise many questions, among them, the legality of using offshore tax-free havens.

Some of the individuals named such as President Sebastian Piñera of Chile, Guillermo Lasso of Ecuador and Luis Abinader of the Dominican Republic are proponents of free markets and vocal advocates of a free-society. Still, while some conservative leaders have recently come under scrutiny for utilizing existing financial structures to safeguard their assets, such safeguards can sometimes fall within the scope of the law.

The Left, while not prominently implicated in the recent leak, is not blemish-free.

In this special report, ADN America takes a closer look at some of the accusations arising from the recent Pandora leak, and the status of other recent financial crimes accusations and prosecutions that have implicated or cast suspicion on Central and South American heads of state from the Panama Papers leak in 2016 and other evidence trails.

Offshore transactions under scrutiny from the Pandora Papers

Chile

Chilean President Sebastián Piñera faced impeachment after the legislature’s lower house voted to refer his case to the senate over allegations of wrong-doing in his family’s $152M sale of their share in Andes Iron’s recent Dominga project, a $2.5 billion copper and iron mine located 40 miles north of La Serena. A contract located by the project, suggests the first $138M of the sale was made in 2011 through shell companies registered in the British Virgin Islands, the Guardian reported.

Last week, the Chilean Senate voted against removing Pinera from office, finally ending an impeachment process. However, his trial in the court of public opinion continues.

Some reports say documents uncovered suggest the final payment of the sale would have required Piñera to refrain from designating the north-central region of Chile where the mine is located an environmentally protected zone.

This fact alarmed some environmentalists since the mine is located only 30 kilometers from the Humboldt Penguin National Reserve, which is reportedly inhabited by more than 500 different species.

The newly uncovered documents raised suspicion, but the ultimate question for Chilean prosecutors was whether they could have demonstrated evidence of an actual crime.

Marta Herrera, chief of the Special Anticorruption Division in the Public Prosecutor’s Office, said her agency would investigate potential bribery-related corruption charges and potential tax violations, Reuters reported.

“The contract signed in the British Virgin Islands was not incorporated into the investigation at that time, so we could say that it is new information,” Herrera said.

An earlier Chilean judicial inquiry, however, examined and dismissed any irregularities in 2017, a fact Piñera has raised to the press since the papers were released.

“I have full confidence that the courts, as they have already done, will confirm there were no irregularities and also my total innocence,” said Piñera as he awaited the Senate’s decision. “As president of Chile I have never, never carried out any action nor management related to Dominga Mining.”

One assertion made by Piñera’s office last month was key in his defense—that the president’s first term as president from 2010 to 2014 had not started when the deal was agreed upon, and that Piñera placed his holdings in a blind trust in 2009 before the transaction occurred.

To prove criminal intent, prosecutors would have had to prove the transaction was illegal, and that Piñera was either aware of the transaction or helped or helped facilitate it.

Ecuador

According to leaked documents and a subsequent investigation by El Universo, Guillermo Lasso, the first free-market friendly president Ecuador has seen in nearly 15 years, controlled 14 offshore companies, based primarily in Panama. At first glance, the revelation sounds incriminating, but the details demand a second, closer look.

Newly released documents reveal that Lasso closed these companies after socialist Rafael Correa’s past government passed a law banning candidates from owning companies located in tax havens.

But Lasso maintains his innocence by claiming he operated in safeguarded jurisdictions because national legislation prevents bankers from investing in Ecuador, and that 10 of the companies in question have been inactive.

Lasso also denies any relationship with the other four offshore companies, and insists he did not profit, El Pais reported.

“Neither when submitting my candidacy, nor since then until now, have I violated the aforementioned prohibition,” he said.

On Friday, Fernando Villavicencio, President of the National Assembly’s Audit Commission, published a report that found that Lasso “is not a direct or indirect beneficiary” or a “director or officer of any company located in a tax haven.”

The report further explains how Lasso has not had any connection to any offshore business since he became a candidate for the Ecuadorian presidency on Sept 23, 2020.

Luis Espinosa Goded, a professor of economics at the University of San Francisco in Quito, told ADN America the trial against Lasso is political, saying it “has been an authentic farce.”

After all, Ecuadorians have been aware of Lasso’s financial dealings for years.

More importantly, however, the fact Lasso publicly disclosed and then subsequently separated himself from his offshore dealings in 2017 after the Correa administration passed legislation to try to limit his presidential run could negate any potential criminal liability the embattled president may have.

To this effect, Espinosa posits the Correista opposition may have an ulterior motive for spending so much time and energy to create suspicion around Ecuador’s free-market president, even though there is no evidence against him.

“It could be that they're nervous because [Alex Nain] Saab [Moran] is in the United States and Saab could reveal everything that he knows about the Correistas,” he explained.

Saab, a Colombian businessman widely considered to be Nicolás Maduro's front man, is currently being held in custody in the United States for money laundering, after being extradited by the U.S. Department of Justice from the Republic of Cabo Verde. The effect of this could be disastrous for the Correistas international public image.

Whatever the case, there is hope the truth will come to light.

Out of 137 legislators, 105 voted in favor of an investigation to “clarify” whether or not Lasso had broken Ecuadorian law or committed an “ethical” offense.

Dominican Republic

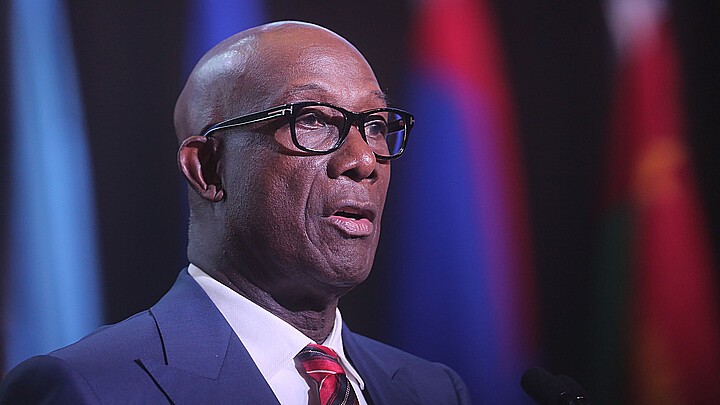

Another Latin American president the Pandora Papers cast suspicion on is Dominican President Luis Abinader, who ran a successful business career in the hotel sector before entering politics.

Documents obtained during the leak suggest the Dominican leader is linked to two Panamanian companies called Littlecot Inc. and Padreso SA.

Still, a recent report from El Pais indicates both companies were formed before Abinader took office and were used to manage assets in the Dominican Republic.

Dominican media outlet Noticias Sin reported that shares of both companies were listed as “payable to the bearer,” making it possible to hide the actual, “beneficial owners,” a phrase used in U.S. Securities law to describe someone who enjoys shared or sole voting rights in a stock. It can also include anyone who controls or influences a client or person on whose behalf a financial transaction is being conducted.

The Abinader family publicly registered as beneficial owners after the passing of legislative reform in 2018 that required them to do so, and upon becoming president in 2020, Abinader publicly declared ownership of nine offshore companies, which he controlled through a trust.

Abinader defended his ties to the offshore assets, arguing that until recently, the Dominican Republic had not issued corporate laws that prevented companies from carrying out operations abroad.

Other conservative former leaders implicated by the leak include former Colombian presidents César Gaviria and Andrés Pastrana, along with former Argentine President Mauricio Macri.

The lawful benefits of tax-havens

While the leak has forced a public conversation surrounding the legality and ethics of utilizing tax havens, some of the dealings outlined by the media may not necessarily be illegal.

In countries as politically and economically unpredictable as those in Latin America, some have defended such action on the basis of financial security. While corruption and money laundering have no legal or moral defense, tax competition and the utilization of tax havens may have some ethical economic utility.

“People often do this in the Central and South American region because sometimes keeping big balances in bank accounts makes them subject to kidnappings for ransom and extortion,” Miami tax attorney Marcell Felipe told ADN America. “Once a criminal enterprise or would-be kidnapper knows exactly how much money a person has in their accounts, they know how much to demand when asking a victim’s family for a ransom or proof of life.”

A Dec. 2019 Duke University study by Professor Juan Carlos Suárez Serrato found that an IRS rule that increased corporate tax rates and decreased access to tax havens for U.S. based multinational companies had the perverse effect of resulting in lower domestic investment and employment.

Philip Booth, a professor at the Institute of Economic Affairs in London, wrote, “Offshore centers allow companies and investment funds to operate internationally without having to abide by several different sets of rules and, often, pay more tax than ought to be due.”

This ultimately allows them to invest more in local markets and human capital instead of helping fund state corruption, advocates argue.

“Tax havens allow the honest to shelter their money from corrupt and oppressive politicians,” Booth added.

This point may explain why under the leadership of Rafael Correa, Ecuador became “the first country in the world to bar politicians and public servants from holding assets in tax havens,” according to a 2017 press release from the Ecuadorian Chancellery.

Tax havens also encourage sound domestic tax policy, argues former Cato Institute Senior Fellow Daniel J. Mitchell.

“Simply stated, when politicians have to worry that jobs and investment can cross borders, they are less likely to impose higher tax rates and punitive levels of double taxation.”

This, Mitchell argues, is beneficial as lower tax rates are more conducive to job creation and entrepreneurship and reducing tax biases against capital formation can help improve growth by increasing savings and investment. Ultimately, he says, this helps the poor.

Still, Prof. Espinosa raises interesting questions regarding the language surrounding “tax havens.”

“In the Hispanic world, we refer to tax havens as tax paradises. So, ultimately my question is, would we need tax paradises if there weren’t such a thing as tax hells?”

What about the left?

Latin America’s left-leaning politicians have so far managed to stay out of the recent headlines brought about by the release of the Pandora Papers, but many of them have been identified in illegal dealings throughout the past decade that led to prosecution and even extradition from the United States.

Below, ADN America reexamines several Central and South American countries and the recent criminal cases and scandals that resulted in the criminal prosecution of heads of state and some instances indictments, and extradition, resulting in both acquittals and convictions.

Brazil

Following an earlier vote-buying scandal resulting in the Brazilian attorney general charging 40 politicians, the Public Ministry accused former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva in 2015 of using his power to help award government contracts to the Odebrecht corporation, a construction giant throughout Latin America.

Prosecutors alleged Lula pressured the Brazilian Development Bank to finance projects in Angola, Cuba, Ghana and the Dominican Republic.

Later that summer, the company’s president, Marcel Odebrecht and other executives were arrested for allegedly paying $230 million in illegal bribes to political officials. Several months later in March 2016, Brazilian law enforcement agents made the bold decision to raid the president’s home, and Lula was detained for questioning.

Despite some maneuvering to shield Lula from criminal charges with political immunity, Brazilian prosecutors indicted him in September 2016, accusing him of masterminding a broad corruption scheme.

The charges created a political uproar as many of Lula’s left wing supporters came out to show their support, demanding his release.

In 2017 he was convicted by a lower court after being identified as the primary beneficiary of a corruption scheme within Petrobras, a state-owned Brazilian multinational petroleum corporation.

According to prosecutors, the former Brazilian premier had been given a beachfront apartment in return for his help in winning contracts with Petrobras at inflated prices. After an unsuccessful appeal, he was sentenced in 2018 to 12 years in prison on charges of money laundering and corruption.

Odebrecht, the Brazilian corporation from which the scandal originated ultimately signed a plea deal in which it admitted to funneling $788 million in bribes to various countries throughout the western hemisphere.

The deal, which required the company to pay $3.5 billion in penalties became known as “the end of the world deal,” and was described by the U.S. Department of Justice as the “largest foreign bribery case in history.”

In July 2019, Telegram messages between the judge and prosecutor in Lula’s case were leaked, and it was implied the government had colluded with the courts to imprison Lula to obstruct his candidacy to run for reelection in 2018. The messages created international debate as to whether Lula was targeted for prosecution, and his attorneys made an international appeal for support.

They sought assistance from the U.N. Human Rights Committee and from prominent U.S. officials and media, eventually garnering the support of The New York Times, author Noam Chomsky and several U.S. Congressional officials including socialist U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, all of whom made a plea that Lula’s conviction should be overturned.

In March, a judge at the Federal Supreme Court overturned Lula da Silva’s convictions, and the decision was ultimately upheld by the Brazilian Supreme Court.

Argentina

In Argentina, former President Nestor Fernández de Kirchner has faced multiple charges since leaving office in 2007 when he stepped aside and supported his wife, Cristina Elisabet Fernández who served as president until 2015, and recently returned in 2019 as the country’s vice-president. Nestor, who died in 2010 and his wife both identified themselves as Peronists, and Cristina is the second woman to serve as Argentina’s head of state.

In December 2017, as a result of the previous 2016 Panama Papers leak an Argentinian court indicted and charged Fernández de Kirchner with high treason over allegations that she helped cover up Iranian involvement in the 1994 bombing of a Jewish community center in Buenos Aires.

That case took bizarre series of turns, especially when in 2015 the prosecutor, Alberto Nisman mysteriously died of a gunshot wound the night before he was expected to reveal damning, new evidence.

In Sept. 2018, a separate indictment also charged her with accepting bribes from construction companies in exchange for contracts during her eight years in the presidency.

As a sitting senator who served from 2017-2019 however, Fernández de Kirchner enjoyed immunity from prosecution, and all charges have since been dropped.

“During the government of Néstor Kirchner, an illegal collection system was put into operation that continued during the presidency of his wife, Cristina Elisabet Fernández,” the judge wrote in the indictment. Fernández and her husband “were the ones who gave the directives and orders for the development of the maneuvers investigated, as well as the final beneficiaries of them.”

The New York Times implied the strange legal development may be driven by corruption, writing, “The unanimous ruling by a three-judge panel is the latest courtroom victory for Mrs. Kirchner, who governed the country from 2007 to 2015. It follows a pattern of Argentina’s judiciary showing leniency toward politicians when they are in power and heightened scrutiny when they leave office.”

Ecuador

Former Ecuadorian President Rafael Correa whose 10-year presidency from 2007-2017 was part of the Latin American ‘Pink Tide’ in a shift toward socialism, was recently sentenced to eight years in prison over corruption charges. Initially issued a warrant for conspiring to kidnap political opponent Fernando Balda, Correa, was ultimately sentenced to eight years in prison for accepting “undue contributions” from 2012-2016 in exchange for awarding state contracts to select businesses. He is reportedly living in exile in Belgium.

He has since been banned Correa from participating in politics for 25 years.

The list of Latin American leaders sent to jail for corruption also includes former presidents Alejandro Toledo of Peru and Ricardo Martinelli of Panama.

Panama

Ricardo Martinelli of Panama was ultimately acquitted and released by a Panamanian judge in his own country, but he shares something in common with former Gen. Manuel Noriega whose drug trafficking schemes led to the U.S. invasion of Panama in 1989. Although Martinelli was never accused of drug trafficking, like Noriega he was detained in the U.S. by federal authorities.

Martinelli, who served as Panama’s 36th president from 2009-2014 was issued a ‘red notice’ request for international arrest by INTERPOL after Panamanian authorities accused him of engaging in illegal wiretapping and surveillance of more than 150 people including journalists and opposition leaders.

Martinelli was detained in Miami by U.S. Marshals in 2017 and extradited to Panama in 2018 where he awaited wiretapping charges under house arrest. In 2019, a panel of Panamanian judges found him not guilty and released him from home detention.

Peru

Alejandro Celestino Toledo Manrique served as Peru’s president from 2001 to 2006 after leading the opposition against Alberto Fujimori whose ten-year term essentially crushed the Maoist Shining Path terrorist organization after several years of committing widespread acts of violence across the country.

After losing his first challenge against Fujimori in 1995, the political party Toledo founded—Peru Possible—gained momentum across the country. In 2000, he successfully challenged Fujimori once again centering his campaign around creating 400,000 new jobs, raising wages and improving social infrastructure.

Toledo’s victory was memorable since he was the first indigenous person to win a presidential election in Peru, and when he announced victory from his hotel room, he wore a red headband in the spirit of ancient Inca warriors. But quickly, the vote began to turn in Fujimori’s favor, and by the end of the night neither candidate had a clear majority and the U.S. State Department declared the election “invalid.”

Toledo declined to have a runoff election and instead petitioned international organizations to deny Fujimori, who began his third term as president, political recognition. Protests shadowed the Peruvian Congress until violence erupted and an explosion killed six people. In the midst of accusations that Fujimori’s allies were tied to the violence, he called for a new election and agreed not to run as a candidate, instead of emigrating to Japan.

Toledo won the new reelection and served for six years until the constitution was amended to restore a ban on immediate reelection, which prevented him from running again in 2006. He ran for reelection in 2011, but trailed significantly behind a known leftist former military officer, Ollanta Humala who also defeated Fujimori’s daughter, Keiko.

In February 2017 Toledo became a visiting scholar at Stanford University. That same year he also faced an arrest warrant from a Peruvian judge after he and his two successors were accused of accepting millions of dollars in bribes from Odebrecht.

The Peruvian government classified the former president as a fugitive and offered a $100,000 reward for his extradition, which was recently granted by a U.S. District Court on Sept. 28. The case is pending.

While both sides concede that corruption and theft of public funds is wrong, the debate surrounding the legality and economic benefits of tax havens and competition continue as journalists continue to wade through the Pandora Papers and the controversy they continue to inspire.

Only time will tell if the information contained within the papers is illegal and leads to criminal convictions for public officials. Whatever their fate, several heads of state in the Central and South American region have found themselves embroiled in major criminal corruption scandals. Some have ultimately overcome convictions and some have not.