Politics

Amazon rainforest countries hold conference in Brazil to combat deforestation and organized crime

For the fourth time in 45 years, South American leaders whose countries connect with the Amazon rainforest are meeting to discuss how to protect the region and combat the growing problem of organized crime in the region

August 9, 2023 9:14am

Updated: August 9, 2023 9:22am

For the fourth time in 45 years, South American leaders whose countries connect with the Amazon rainforest are meeting to discuss how to protect the region and combat the growing problem of regional organized crime.

The Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ACTO) is meeting Tuesday and Wednesday this week in the Brazilian city of Belem, a rare occasion which last took place 14 years ago.

The rainforest is the largest rural area of its kind, spanning across two-thirds of Brazil while covering twice the area of India. The remaining third covers seven other countries and one territory. Those areas include Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Peru, Guyana, Suriname and Venezuela.

The conference, which began Tuesday morning hosted presidents from Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, French Guiana, Guyana and Peru. Leaders from Ecuador Suriname and Venezuela did not attend.

The attending leaders hope that by heralding the cause of the Amazon rainforest they can also seek joint solutions about the growing problem of transnational organized crime.

Addressing environmental concerns impacting the Amazon rainforest

All the participating ACTO countries previously ratified the Paris climate accord, which requires signatories to set targets for reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

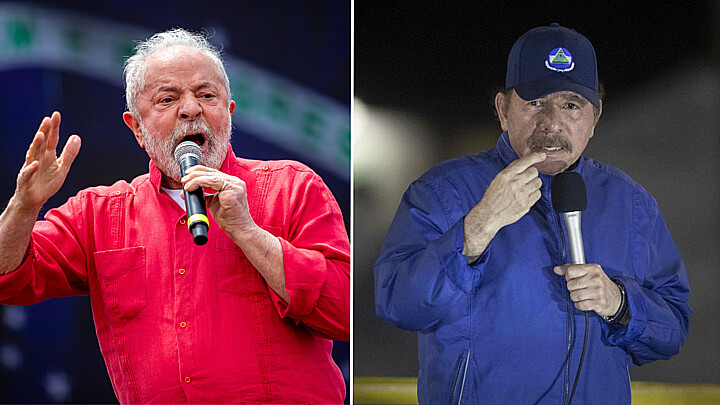

Prior to the conference, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said he hoped the Belem summit would be a catalyst to reigniting ACTO, which he believes can have more hands on impact in the South American region.

“I have great expectation that, for the first time, we will have a common policy for action in the Amazon,” Lula told reporters in the Brazilian capital on Aug. 2.

For Lula, the summit may have political ramifications since the move is his second attempt to reignite the alliance. He tried, but failed to do so across the Atlantic in Copenhagen in 2009 during his previous presidency, but was only joined by Guyanese president Bharrat Jagdeo and then French President Nicolas Sarkozy.

“The context is totally different today,” Brazilian Environment and Climate Change Minister Marina Silva told The Associated Press. “President Lula is very determined that this summit will not be just another event with no real outcomes for the decisions that will be announced here.”

Silva said this summit, 14 years later will also examine what could happen and when 20% to 25% of the forest is destroyed. Some scientists speculate a decline in rainfall could result in such deforestation and transform more than half of the forest to a tropical savannah, with biodiversity loss but an increase in carbon dioxide.

To date, different countries have made different commitments about their approach to the Amazon.

Brazil and Colombia have decided to stop deforestation by 2030 while other nations have abstained from making such commitments.

So far, Lula has created six of 14 new indigenous territories and has promised to restore Brazil’s official climate commitment, which requires a 37% decrease in emissions by 2025 from the country’s original numbers in 2005.

Petro has proposed an ambitious 30-year plan for reaching carbon “neutrality” by 2050, which the aim of reducing its greenhouse gases by 51%.

Both leaders have tried to stand out on the world stage as taking charge on the environmental issue, while Brazil remains a major producer of agricultural goods and Colombia a major driller of oil.

About 20,000 people from different Amazon countries have reportedly arranged 400 parallel events, hoping to lobby government officials about their concerns.

Combatting organized Crime in South America

Another country actively participating in the conference is Ecuador. President Guillermo Lasso, a known conservative in the region has made commitments to spearhead his country toward an pro-environmental transition that will reduce deforestation and also create a safe bio-corridor for animals.

But Lasso’s main concerns are aimed at the conference’s other objective: combatting organized crime and narcotic trafficking.

To combat the growing problem of organized crime in the region, Brazil’s Lula has announced the large South American country will build a new headquarters for international law enforcement cooperation in Manaus, known as the largest city in the Amazon.

The new center would hope to create a new era of joint cooperation so that individual nation state raids have been ineffective.

“You’re seeing a creeping recognition ... of the importance of addressing crime in the Amazon,” said Rob Muggah, co-founder of the Igarape Institute, a security-focused think tank. But the effort hasn’t been serious yet, he added. “We’re still tackling it with band-aids.”

Prior to Lula’s announcement, the region has seen few joint transnational efforts due to regional conflict and disagreements. The countries attending this week’s ACTO conference are hoping they can use the call of environmental preservation as a vehicle to also inspire cross border cooperation to combat organized crime.

The last such transnational efforts were four and five years ago.

In 2018 regional states signed the Escazu Agreement which established a public right to obtain information about how governments were making decisions about the environment.

In 2019, the signatories also signed a companion treaty known as the Leticia Pact, aimed at improving environmental protection.

Four years later, Lula said he now hopes a new “Belem Declaration” will become the regions’ joint declaration to work together as they prepare for the upcoming global climate conference in November in Dubai.

The Brazilian leader has made Amazon preservation a large part of his platform. During his first seven months in office, some reports suggest the rainforest has suffered a 42% drop in deforestation.

Lula has sought international aid from Western European countries such as Germany and Norway, and is turning to other donors to contribute to Brazil’s Amazon Fund for sustainable development. He has also tried to find support from the leaders of other countries that also have large rainforest regions such as Indonesia, the Republic of Congo, and the Democratic Republic of Congo.